Sea lice

Sea lice attach to and feed on Atlantic salmon and other related species, such as trout and char. It is not uncommon for wild salmon to have sea lice to some extent, but when thousands of salmon are placed in an open sea cage, it creates ideal conditions for the lice to multiply.

Key factors

- Experts of the fish farming industry claimed that sea-lice would not become a problem in Iceland due to the low temperature of the sea. That turned out to be wrong and the industry has had to poison the fjords on several occasions to battle sea-lice outbursts.

- In 2020 Icelandic authorities suggested that 15 times more sea-lice would be allowed in net pens here compared to Norway.

- About 800.000 lumpfish were deployed into Icelandic net pens in 2020 with the sole mission to eat sea-lice and die and rot in the pens.

- From 2017 – 2020 pesticides have had to be used in at Arnarfjörður, Dýrafjörður and Tálknafjörður.

- With rising ocean temperatures and increased biomass the sea-lice will become an even more serious problem – with devastating results for wild stocks and the environment.

- Sea lice are parasites that live in the sea that feed on the mucus, blood, and skin of salmon.

- When thousands of salmon are put into an open net pen, it creates an optimal environment for salmon lice to multiply.

- Juvenile smolts are especially sensitive to lice. Entire wild salmon stocks have been largely decimated as a result of their proximity to open net pens.

- Aquaculture companies have long claimed that sea lice would not be a problem in Iceland due to cold sea temperatures. This proved to be wrong, and now poison is often used in order to tackle the sea lice problem.

- Increasing sea temperatures around Iceland mean that sea lice issues are expected to become more common and significant, with increasing harmful impacts on the environment.

Sea lice

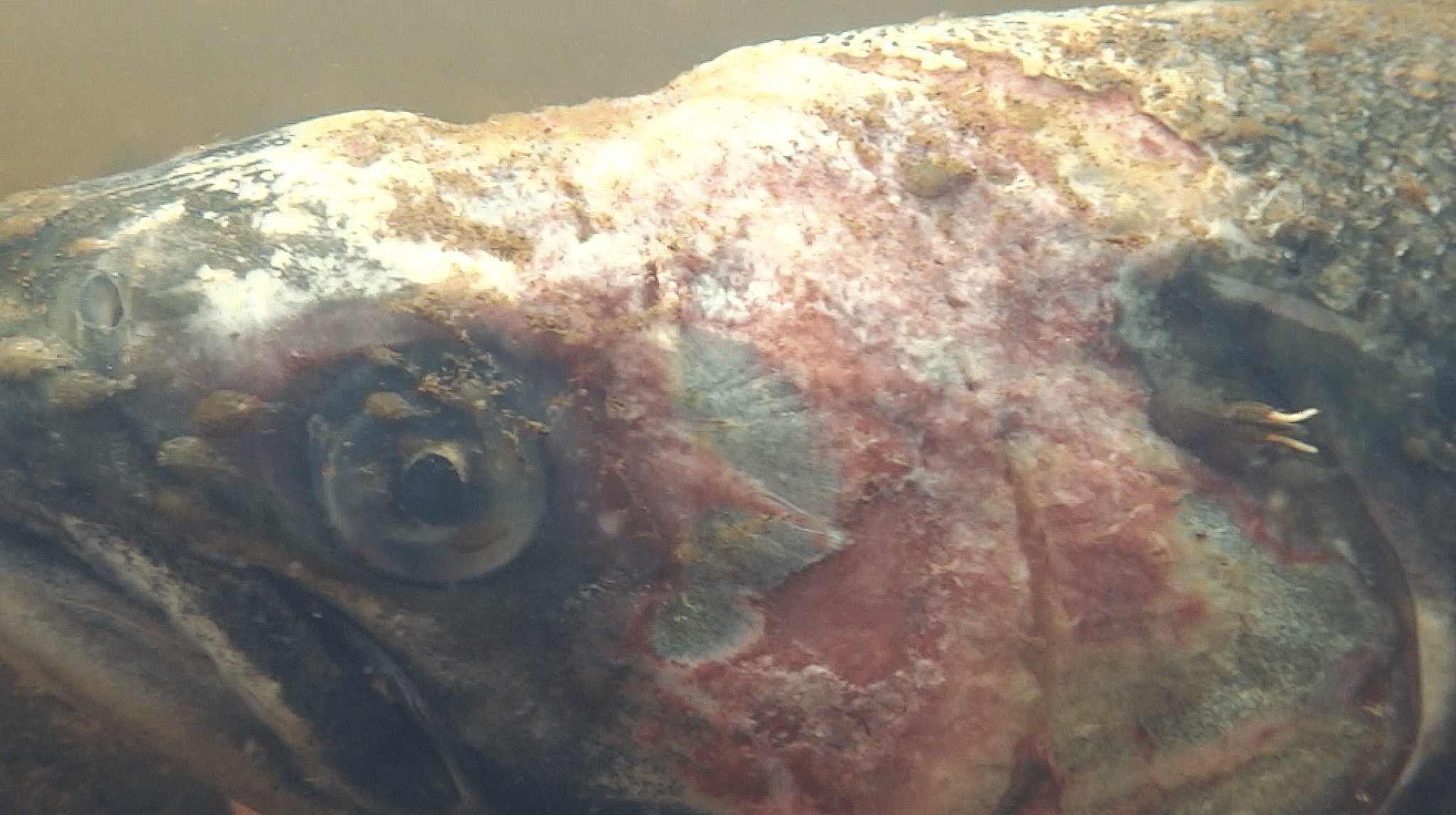

Sea lice live on the skin cells, mucus and blood of the fish, and in large amounts they can eat the fish alive. The consequences for the fish can be anemia and fluid imbalance, and in some cases it may lead to death.

Open net pens provide no barrier to the outside environment, giving sea lice easy access to wild fish. Salmon smolts are small and especially vulnerable to sea lice. Entire stocks of wild salmon have become nearly extinct due to close proximity to open sea cages infested with sea lice.

A common treatment for sea lice involves pumping poison into open net pens, which then freely passes into the surrounding waters. It is common for sea lice to become resistant to the poison, leading the aquaculture industry to try ever-more toxic solutions, each one worse than the last.

Fish farming companies in Iceland firmly stated that sea lice would not be a problem in Iceland because the sea is too cold – a claim that proved to be false. Poison has been used repeatedly to try to keep the lice in check.

Aquaculture in Iceland today is a rather small industry, but plans for it to multiply in size will cause the problem to multiply, as well, and along with it the associated negative impact on nature. Sea lice is one of the biggest problems facing the aquaculture industry. The only real defence against it is closed containment or land based fish farming.

Sea lice are particularly apt to spread between fish when they meet in fjords, estuaries, or shallow waters outside estuaries. The effects on salmon are numerous. It is a parasite that has an adverse affect on the health of the fish and their chances of survival at sea. Sea lice on farmed salmon can attach itself to wild salmon, as well as wild char, which inhabits shallow seas and coastal areas, precisely where the most largest amount of sea lice from fish farming exists. Sea lice also results in the use of toxic substances used as pesticides, which adversely affect other species in the marine environment.

In 2017, Samuel Shephard and Patrick Gargan published an article on the effects of sea lice on the passage of wild salmon in the Erriff River on the west coast of Ireland. They used data that spanned a 26-year period, and evaluated the impact of sea lice on the number of salmon returning after a year in the sea. The results were decisive: a major infection of sea lice during the summer led to poor recovery in salmon runs the following year. Sea lice affected the total number of fish in the river and hence the fishing each year. These findings correlate to the reports of Forseth’s and and his partners, which found that sea lice are a persistent problem in Norwegian fish farming. Attempts to reduce infestation and its effects have little effect due, in part, to the industry’s continued growth.

Pesticides used against sea lice accumulate in nature. In 2017, Langford and partners examined the diffusion of five pesticides in areas surrounding fish farms in Norway. They found three active substances (diflubenzuron, teflubenzuron, and emamectin benzoate) at considerable concentrations in sediment and fluid samples at 40% of sampling sites. Persistent lice infections lead to a higher load of these toxins in nature.

Pesticides used to treat sea lice adversely affect wild species in the ocean, especially in the immediate vicinity of fish farms. Langford’s team found toxins in shrimp at one station, in concentrations that could affect molting. Another scientist, Kristine E. Brokke, also found that certain drug compounds used to treat sea lice adversely affect wild shrimps.

There is every reason to worry about sea lice and the chemicals used to treat them. Use of these chemicals has multiplied in the last decade. Between 2008 and 2012 in Norway, the amounts used vastly increased, from 218 kg to 6,810 kg. (Norwegian IPH). And as with all other medications and toxins, sea lice develop a tolerance as a result of increased drug use. The chemical warfare against sea lice calls for larger doses and stronger substances, while the lice continue to develop resistance.

With sea temperatures around Iceland increasing, it is assumed that the lice problem will be much more common and more serious. Warmer waters see lice infestations increase in open net pens. The resulting transmittal to wild stocks, especially when salmon smolts are in a delicate adaptation phase in salty waters, has a profound effect on survival at sea.

North American, Irish, and Norwegian scientists, as well as aquaculture representatives from the Faroe Islands, agree that lice problems come up everywhere, sooner or later, when salmon is farmed in open net pen. Here in Iceland, people were reluctant